Mankind was not cognizant of the depth of the ignorance that, since primordial times, had underlain the existence of live on Earth. It was in those primordial times that the first organisms to respond to the Moon began accumulating concepts of it. Creatures were moved to and fro in the waters; they were brought to the shallows and onto dry land.

No air is out there, sayeth the falling heart.

Eventually, as in fishes and turtles, they laid their eggs near the shore or on land itself. They were drawn by the Moon, and those which had eyes saw the Moon. Yet they never had a concept that the Moon contained water, or did not contain water. They did not have a concept that the Moon contained air or did not contain air, or that it would be devastatingly lethal if they were there on the Moon and not here on Earth.

Those stark facts and absences of facts were what passed for instinct. Concepts liked these spanned all time, until human beings began to make stone tools and use fire in preparation for the actual event of walking on the Moon. Thus each person, on presenting that goal to others, presented a destiny, which they could accept or fight, that by itself would, without air to breathe, inevitably mean deaths.

No wonder so much war attended the civilizations of Earth during the first ten thousand years of their constructions in the events prior to the first actual, successful explorations of space.

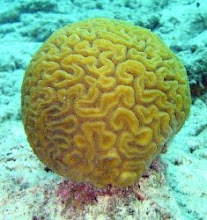

A cenotaph is suggested. It would have a base of basalt or other hard mineral containing shells from ancient clams and oysters, corals and sponges and sea stars. The base would first gradually, then rapidly rise, suggesting the direction of the Moon. Above the ancient base would be layers of subsequent phases in the development of life as it attained greater height. It would have to move quickly from there to the architecture, from pyramids to the wondrous modern forms and machines and to the nobility that triumphed over the primitive, darkness that had dominated the Earth so deeply.

After all, the expertise attained by cruel zero-sum predation was among the skills and capabilities of those who designed and flew the craft that did, finally and triumphantly, attain the Moon. It is signal that now the intelligence designing space flight is not zero sum competition.

The result is so significant that it is not even possible to regret the vast destruction of war, even while recognizing that in principle, it was never necessary to kill anything, to send machines and human beings to the Moon, and bring the living beings back to Earth safely. It was never necessary to kill a single human being or other living thing, to reach the Moon. It is possible to mourn the loss. Earth will do that for a long time.

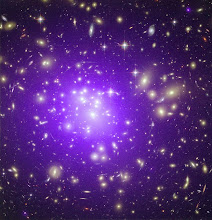

The path of development had been from total ignorance of the lethality of the Moon's vacuum. It was ignorance sustained through a billion years of cruel and often carnivorous predation. During all that time, not a single cell or organism or creature guessed that the seemingly inevitable threat to life came not from opponent or partner, but from the vacuum of space on the Moon's surface where a living being from Earth would inevitably stand because life had decided to go there, or from devastating energy as if crushed by waves against rocky shore.

Those who died trying, in the centuries preceding triumph, did not die in vain, but only in the aftermath of total knowledge is it clear that the carnage was not necessary to the triumph. A new World Class Cenotaph now should mean a great deal. It must transcend vast time and distance; the existence of places that are intrinsically lethal, and the depth of instinct in the human soul or it will be regarded as temporal.

Monday, November 5, 2012

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)